Lou Harrison: American Musical Maverick, by Bill Alves and Brett Campbell, available on Amazon.

By Bill Alves

In honor of the centennial of composer Lou Harrison, composer and author Bill Alves is blogging about the Harrison works on the concerts of MicroFest 2017. Alves and Brett Campbell are authors of the new and definitive book on Harrison: Lou Harrison: American Musical Maverick, and much of this information comes from that volume. On April 21 in UCLA’s James Bridges Theater in Melnitz Hall, MicroFest will be presenting a program of Lou Harrison in Film and Music. In anticipation of that event, Bill Alves and Brett Campbell wrote this passage about Harrison’s own time at UCLA. Bill Alves will be available to sign copies of Lou Harrison: American Musical Maverick.

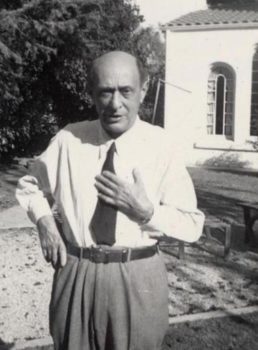

Lou Harrison c. 1943

In 1942, after his youthful years studying with Henry Cowell, writing numerous dance scores, and collaborating with John Cage, Lou Harrison felt that he had outgrown arts scene in San Francisco. But it was more than just the promise of a position with a dance company that lured him south to Los Angeles. He harbored the hope of studying with one of his musical idols, Arnold Schoenberg. Many people know Harrison for his later music of ravishing tonal melodies, sunny textures, and Asian influences. Yet, as different as it may sound at first, the atonal experiments of crucial period emerged from the same expressive aesthetic and are important in understanding his later innovations.

Copland c. 1943

First, Harrison found an apartment in Hollywood, just across from the famous wrought iron gates of Paramount Studios (he was nearly run over by Bob Hope one day). Through his contacts, he met Aaron Copland, who was in Hollywood working on film scores, and Copland’s voice echoes in a symphony that Harrison was working on at the time. (Although the symphony in this form was never completed, this movement became the finale to Harrison’s Elegiac Symphony in 1974.) Just as important, he got a job accompanying dance classes at UCLA, where Schoenberg, a war refugee, was teaching.

Schoenberg and his assistant, Harold Halma

So it was that just before the spring 1943 semester, Harrison carried a handful of scores and knocked on the door of Schoenberg’s assistant, who led him into the 68-year-old composer’s office. Startled and twitching, the modernist master flipped through the scores and asked, “Why do you want to study with me?”

For years Schoenberg’s music was “just a total absorption” for Harrison. “The very rich texture sonically, plus the intensity of the emotional power [was] unlike anything else for me.” Most people knew Schoenberg as the avatar of atonality, the inventor of the twelve-tone method of composition, which was blamed for bringing to midcentury music a fearsome intellectualism amid dense complexity. However, Harrison understood that the truth was nearly the opposite, that Schoenberg’s music represented the distillation of late Romantic expressionism. Schoenberg recognized that such expressivity was only possible through rational discipline, and Schoenberg’s American students often disappointed him in this regard. Cage had already warned Harrison with tales of Schoenberg’s harshness to students who did not measure up to his rigorous standards.

Schoenberg looked up from Harrison’s scores. You can join the class, he said.

UCLA c. 1938

But Schoenberg impressed Harrison not as a fearsome pedagogue but as a teacher with a keen mind that would instantly focus on the expressive goals and form of any style of score they brought into class. Despite his nervous manner and sometimes halting English, the class’s compact size allowed for extensive personal feedback from the teacher, who invited students to bring their works to class. Even in Los Angeles, the horror of his adopted country at war with his homeland, as well as the Nazis persecution of Jews, was never far away. Schoenberg would duck down in mid-sentence when the buzz of passing aircraft came through the windows. Or, he might shush the class to listen to a birdsong.

The first major composition of Harrison’s year in Los Angeles emerged from the twin influences of Schoenberg and the formidable technique of LA pianist Frances Mullen. Mullen and her husband, writer Peter Yates, had inaugurated a daring contemporary music concert series in the loft of their modernist Silver Lake home. She invited Harrison to contribute a piece for this series, known as Evenings on Roof and still vital today as Monday Evening Concerts. Harrison often discussed with Yates his fascination with the processes of medieval music and their reflection in scholastic philosophy of the period.

Schoenberg at his Brentwood home c. 1942

As part of a twelve-tone piano suite, Harrison resolved to write a conductus—a medieval form built above the foundation of a core melody, the cantus firmus—in which a series of variations lay atop this melody made up of all the permutations of the twelve-tone row, or sequence of tones. He contrasted a series of variations on rapid staccato exchanges of chords with singing melodic lines, but then he began to bog down. The twelve repetitions of twelve whole notes that underlay the structure soon became tedious, precluding shaping of a larger structure. He resorted to making the variations around the cantus firmus increasingly complex, but he wasn’t very far down this path when he realized that he had reached a nearly impenetrable density—and a long way yet to go in his structure.

The obvious solution was to ask his teacher’s advice, but Schoenberg’s assistant had bluntly warned Harrison that Schoenberg absolutely refused to look at anything twelve-tone. No composer should dare approach that method, he declared, until he’d mastered conventional tonal styles. Most of his American students could not come close to meeting his high expectations; rumor among the students had it that Schoenberg on occasion had thrown out the entire class in exasperation.

Schoenberg and one of his classes

Nevertheless, at their next meeting, Harrison sat down at the piano in front of his classmates, and started to play. Schoenberg recognized at once that the piece was twelve-tone, but exclaimed, “It is good!” Harrison let out his breath as Schoenberg said, “Continue!” Harrison played as much of the troublesome movement as he’d completed, but Schoenberg was already thoroughly engaged in the piece. He immediately perceived the structure Harrison had established—and just where he’d gone wrong. “Thin out!” Schoenberg admonished. “Less! Thin! Thinner!” Schoenberg showed that the cantus firmus had to impart some structure so that the long string of whole notes did not become pointlessly plodding. He suggested adding variety by making the middle six repetitions into half notes, giving the movement an underlying ABA structure. Freed from the one-way cul-de-sac implied by an unchanging cantus firmus, Harrison suddenly saw new opportunities for variation and internal structure that would make the movement work. Ultimately Harrison’s Suite for Piano would become one of the finest of his early period.

Schoenberg’s advice, Harrison later recalled, “permanently disposed of for me not only that particular difficulty but also any of the kind that I might ever encounter.” The encounter’s value to Harrison extended beyond that single piece. “Simplify,” became Schoenberg’s own cantus firmus to Harrison’s career, steering the young composer away from elaboration and complexity and toward the clarity and transparency of Mozart.